By Jim Tuohy

Every once in a while my old pal Dino calls me when he’s in town and we work out together, usually doing some serious power lifting.

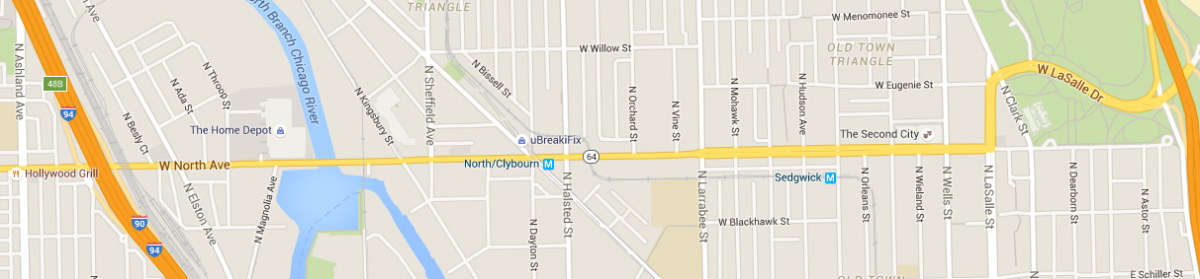

Thus we were lifting a few the other afternoon at the Old Town Ale House when Street Jimmy came in with a bunch of change. Street Jimmy has been written about very humorously elsewhere in this publication by Bruce Elliot, the artist in residence at the Ale House who came about his position by the happy coincidence of being married to the proprietress.

Street Jimmy is a junkie whose main source of legitimate income arrives from begging in the vicinity of North and Wells. When he accumulates enough nickels and dimes and pennies he brings them into the Ale House where the bartender agrees to convert them into dollar bills, since Jimmy’s heroin connection apparently does not consider things like pennies proper monetary units to be used in a respectable dope deal.

In fact, the Ale House bartenders won’t take the pennies, either, only the higher denominations of change. That doesn’t stop Street Jimmy from trying; he always clatters a mass of pennies onto the bar along with nickels and dimes even though he is always refused. Bruce has pointed out that Jimmy’s powers of retention may have suffered a bit by the way he has chosen to conduct his path through life.

“I hated pennies, too,” said Dino, watching the transaction between Jimmy and the bartender.

Dino and I were in the Marine Corps together back in the 1950s around the time of the Korean War. Actually, to phrase our military service as I just did is a bit misleading. Where we were stationed was in downtown San Francisco, and the fighting had ended several months before we enlisted. But we are technically Korean War veterans, and we have a ribbon and the G.I. Bill to prove it.

In those days the Marines had a headquarters and supply building at 100 Harrison Street, almost at the Embarcadero, under the Bay Bridge. Dino had gone in the Corps from McCook, Nebraska, about a month before I had gone in from Chicago, but we ended up at the same duty station, where we carried out office duties when we weren’t detached to Special Services. I played basketball and Dino played baseball. To extend our ball-playing detachments from our regular duties, I used my influence to get Dino on the basketball team in the winter, and he used his influence to get me on the baseball team in the spring.

I looked good in my baseball uniform that said MARINES across the jersey, and I had nice form when I played catch, but I had grown up playing 16-inch softball and I never in my life had played a game of hardball, a game in Chicago we called “league.” However, I had a private conceit that I might be one of those athletes who could master a new sport almost immediately. I found out at the first practice that not only was I not a potential master, I was a menace to the orderly conduct of the game, that I couldn’t hit and I couldn’t field, and that I never would. In the outfield I ran in to catch flies that landed behind me. At the plate, no matter how light the bat, I couldn’t swing it around fast enough to hit even the slowest pitch.

Out of friendship they let me stay on the team, and once in a hastily scheduled non-league game against a pickup team from a destroyer that was undergoing repairs at Hunter’s Point, I got into a game. The game had become so one-sided in our favor that the coach asked me if I wanted to pinch hit. It was a desperate attempt to keep the score down by reversing the logic of baseball strategy—putting in a bad hitter to replace a good one.

Everyone expected me to make an out and help bring the game to a merciful close, but I had been studying the pitcher. I discerned that his deliveries were seldom strikes. Guys like Dino swung and connected on pitches outside the strike zone because they were so easy to hit. My plan, therefore–knowing even the lamest of pitches were beyond my ability to catch up with–was to not swing at anything. I calculated, from my close observations, that the pitcher’s chances of throwing three strikes out of seven pitches were close to zero; he had not done so the entire game. I would take a walk, and I would someday be able to tell my children and grandchildren that in my entire baseball career with the United States Marines I was able to reach base every time I batted.

I stepped confidently in the box, waving heavy lumber; I had no intention of swinging it, so it didn’t matter that I could barely lift the bat off my shoulder . I squinted intimidatingly at the pitcher. The first pitch came, fat and right over the heart of the plate. Called strike one. The second pitch arrived slow and down the middle. Strike two. I knew this couldn’t last; I was too good at calculating odds. Third pitch. Strike three.

We played it safer with Dino on the basketball team. While I could look okay throwing the ball around before a baseball game, Dino was so awful in all aspects of basketball that we didn’t dare expose him to pregame warm up drills. He would drop passes, kick balls into the seats, and launch layups into space. But he too looked good in his uniform so we dressed him for every game and put an Ace bandage over most of one leg. He became our designated best player who was out with an injury, a role he excelled at, putting on a show for the other team, limping and exhorting us to carry on as best we could without him. And of course, if we chose to, we could point out that we were losing games without the services of our star.

Dino had many of the requirements of a good con man. He was handsome in a crooked-nose Marlboro Man kind of way, had a good speaking voice and a direct trustful gaze, and he was a glib liar. It made him a very good panhandler. As Marine PFC’s we were paid about $80 a month, so money was always tight to those of us who were not careful with it. Dino supplemented the cost of our liberty adventures, if need be, with some panhandling. He had developed a successful spiel about being a serviceman stranded without enough money to get the ferry over to the Naval Hospital in Oakland, or to the Marine security detail at Treasure Island or to his duties as a chaplain’s assistant at the Presidio.

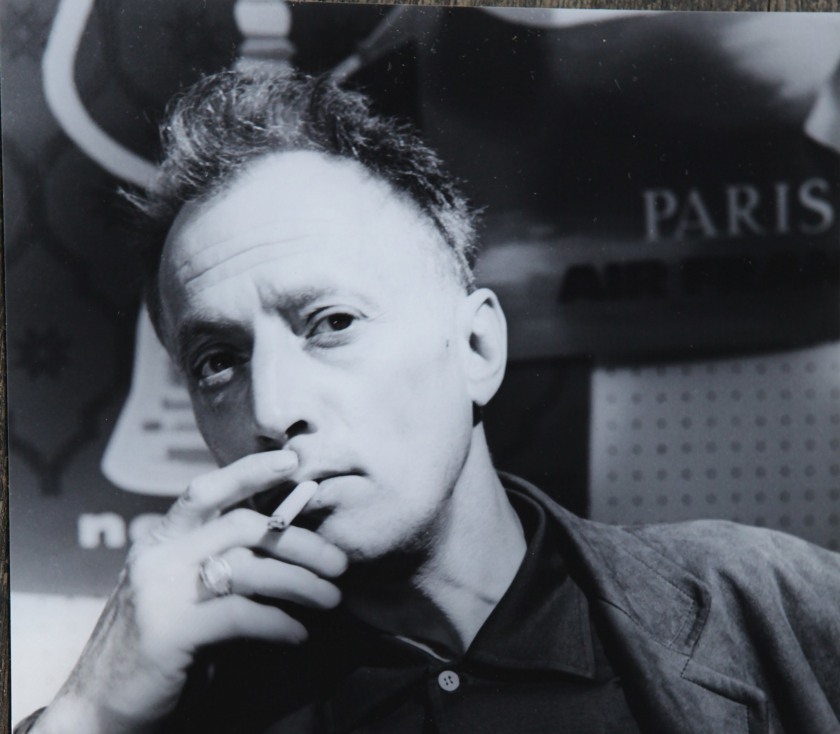

One of Dino’s most successful nights came when we were at the old Hungry I between sets of the Vince Guaraldi Trio and Mort Sahl. We were on the last beers we could afford (at about 35 cents each) when Dino said, “Let me go out and see if I can raise enough for another drink.”

He left and I prepared to make my beer last. But I didn’t have to. Dino was back in no more than ten minutes with something like nine dollars and twenty-five cents. It was enough for us to drink until closing, and then to get a six-pack for the walk back to the barracks.

We were sitting with our six-pack at an empty newspaper kiosk on Market Street when a guy walked unsteadily towards us. He was husky and rugged looking, rather swarthy. He could have been anything, I thought, a drifter, a merchant marine. But he was friendly and talkative and we gave him a beer. His name was Art. Art DiBenidetto. We talked of nothing important, as good natured drunks tend to, and Dino said on payday he was going to buy a watch for his girlfriend’s birthday back in Nebraska.

“A watch?” Art asked. “You want a watch? Come with me.”

Dino and I looked at each other knowing what the other was thinking: This might not be good, but it might be interesting. Warily, we followed Art. We turned a corner and we were in Union Square in front of a granite building where a maintenance man was hosing down the sidewalk.

“Good morning, Mr.DiBenidetto,” the man said as he turned off the hose and unlocked the building’s elegant front door. We went to the second floor where a sign in the door of a store said “DiBenidetto Brothers Jewelers.” Art owned one of the fanciest jewelry stores in San Francisco. He told Dino to pick out a watch for his girl friend. He told me to pick out a watch for myself. We said something like, “No, no, we couldn’t,” but without much conviction.

‘Listen, you guys gave me your last beer,” said Art, who it turned out had been a lieutenant in the Marine Corps in World War II. “That was worth a lot more to me than a couple of watches.”

Actually, I think it was three watches. Dino ended up getting one for himself.

As Street Jimmy scooped up his rejected pennies from the bar at the Ale House, Dino said, “Pennies were a pain–at least a disappointment. I’d get somebody to listen to my story, which was the hard part, but then end up with more pennies than quarters.”

I never panhandled; I never had Dino’s knack, but I once had a banner bottle deposit day.

It was June of 1982 and I was writing a story at the apartment of my beloved Miss Jones, who was off at work. Her apartment was two blocks from Wrigley Field, close enough to hear the crowd roar. I took a break about one o’clock and turned on the TV to Channel 9. A pregame interview was in progress and I discovered the Cubs were about to play the Phillies, which was of only casual interest to me until I found out the starting pitchers were Fergie Jenkins for the Cubs and Steve Carlton for the Phillies–two sure hall of famers. Pete Rose was playing first for the Phillies and Mike Schmidt third, two more hall of famers. Ryne Sandberg was also on the Cubs but it was too early to know he would one day make it to the hall, although I enjoyed watching him, a smooth natural talent. Maybe I could slip out for a while…

The problem was, I had no money, which was no surprise, but after a thorough search of Miss Jones’s stashing spots I found she had left no money around either. But there were some empty pop bottles in the pantry. In an effort to be environmentally sound we had taken to buying Coca-Cola in 8-packs of 16-ounce returnable bottles, each bottle worth a 10-cent refund. There were two 8-packs, worth $1.60. I think at the time it cost $2.50 to get into the bleachers and perhaps $4.50 to get a general admission ticket. There were a few assorted pop bottles in the pantry, most of them quart-sized. When I was a kid these bottles had a nickel return, so it would take a lot of them to get me up to bleacher money, even if they had gone up to a dime. All I could do was try. All those great players were beckoning to me.

I loaded the bottles in an unwieldy box and set out at a fast pace for the Jewel at Southport and Addison. The game was about to start. I waited anxiously as the service desk person did some button-pushing calculations before a piece of paper clickety-clicked from a slot. She went into a desk drawer and pulled out—bills! A five! A couple of ones! A Kennedy half dollar! Refunds on quart bottles were now 25 cents each, much more than the old days. I had more than seven dollars!

I hustled down Addison. I had enough money to get into the bleachers with enough left over for a beer and even a hot dog if I chose. Or I could pay my way into the grandstand and wiggle my way into the box seats, where my distinguished gray hair would make me look as if I belonged. It was a beautiful sunny day. I was almost skipping along with happiness when a thought exploded in my head:

I AM 48 YEARS OLD AND I HAVE JUST RETURNED POP BOTTLES TO GET ENOUGH NICKELS AND DIMES TO GET INTO A CUB GAME. I DID THAT WHEN I WAS NINE YEARS OLD. THIS IS THE EXTENT TO WHICH MY LIFE HAS PROGRESSED? WHY AM I HAPPY?

Still, under achiever as I was, I couldn’t contain my joy. I was seated in the boxes in time to watch the Cubs score five runs off Carlton in the second as they went on to win 12 to 11.

“I thought for a moment there in the Jewel I might have do a you if I came up a little short,” I said to Dino in the Ale House. “I might have to beg outside the park. Maybe I could have said I was a disabled vet.”

“You were, as far as earning power went,” said Dino. “How much does it cost to get into Wrigley now?”

“The last time I went it was seventy-six dollars for seats in the area I paid four-fifty for that day.”

“Where’d you get seventy-six bucks?” Dino asked.

“I didn’t. My friend Andy Rayburn from Canada took me. We have a deal. Whenever he’s in Chicago he takes me to a Cub game. Whenever I’m in Ottawa I take him to a Senators hockey game. So far I’ve never been to Ottawa.”

“Well if that deal falls through you might consider saving bottles,” Dino said. “At an average, say, of fifteen cents each you would only need about five hundred to get enough dough for a good ticket. Getting them to the Jewel would be a problem, though.”

“Or I could wait for you to come to town and you could do your Frisco thing. How long you think it would take for you to raise seventy-six bucks on game day at Clark and Addison?”

“I’m fifty years out of practice, but I would guess about twenty minutes,” Dino said with his direct trustful gaze.

end

You must be logged in to post a comment.